This Is How To Make Your Kids Successful: 4 Secrets From Research

.

***

Before we commence with the festivities, I wanted to thank everyone for helping my first book become a Wall Street Journal bestseller. To check it out, click here.

***

You want your kids to grow up and be more than just… older. You want them to be successful and fulfilled.

But it’s a daunting challenge for a parent. Never mind that the price of 4 years of college looks like a phone number these days. You also get a lot of conflicting advice.

Truth is, there are very few hard and fast rules in the universe (the only definite one being that A/V materials will never, ever function correctly during your presentation.) But trying to get straight answers about good parenting can be downright sanity-straining.

What’s the latest we’ve been hearing? 10,000 hours of deliberate practice, grit, early specialization, tiger moms…

Are you skeptical about any of these? Good, you’ve come to the right place. (Here, take a seat next to me.) Luckily, someone has done the research and has clear answers for us…

The estimable David Epstein, author of the excellent NYT bestseller The Sports Gene, has a new book out that turns a number of these ideas on their head. (And he’s not just a fantastic author – he’s also a new father.)

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World is already one of my “Best Books of 2019.” (It’s so good that I’ll be interviewing David about it, at a live event, on 6/18. If you’re in LA, swing on by.)

Okay, so you want your kids to be successful, happy, and as cool as the other side of the pillow?

Let’s get to it…

1) Children Need A “Sampling Period”

“10,000 hours of deliberate practice to be an expert.” We’ve heard this a lot. And while you can debate the specifics, nobody disputes that all other things being equal, more hours = more good. Which leads a lot of parents to think that you need to start kids on a path to expertise as young as possible.

On the surface, it makes sense. It’s been best illustrated by the story of Tiger Woods. His dad had him playing with putters at 7 months, he was beating adults at age 4, and even beat his own father at age 8. This story has become the stuff of legend. (Heck, his dad even later wrote a parenting book.)

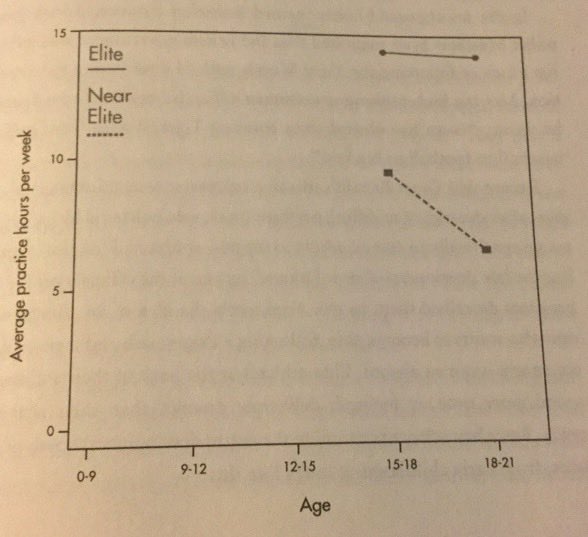

And there’s no doubt — the elites do spend more time on deliberate practice than non-elites. You know it must be true because I have a chart:

So this must mean you have to get your kids started on their destined path as soon as possible to rack up those hours, right? Well, much like my online dating profile, this sounds good at first but turns out to not be very accurate…

Because there’s another athlete’s story you don’t hear as much. This kid didn’t relentlessly focus on one sport. He was skiing, wrestling, swimming, skateboarding, playing basketball, handball, badminton and soccer.

He tried everything and was serious about nothing. It wasn’t until his teens that he started to focus on tennis…

But that kid became Roger Federer.

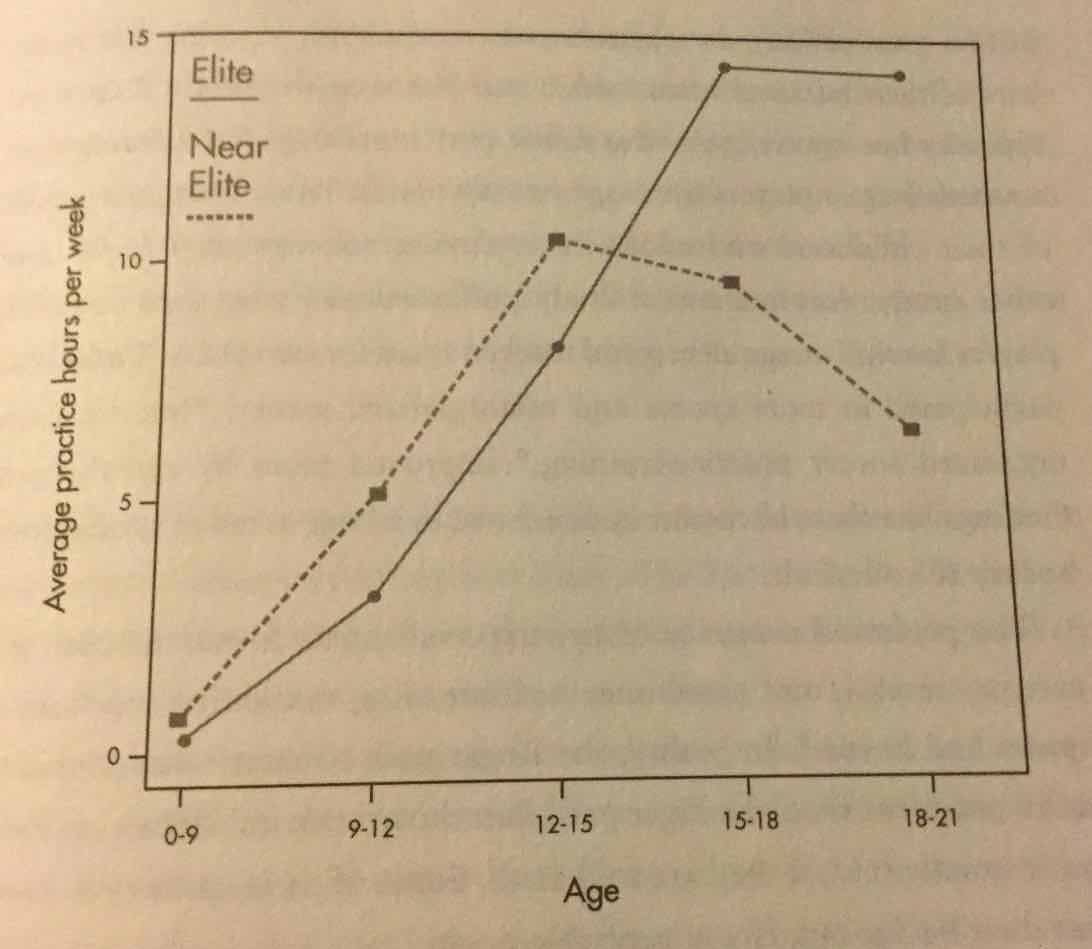

And it turns out that the Roger path is actually much more common than the Tiger path. At young ages, Tiger is the exception, not the rule, among elites:

(Yes, I admit, that was a sneaky gimmick with the charts. Blame David, not me.)

From Range:

Eventual elites typically devote less time early on to deliberate practice in the activity in which they will eventually become experts. Instead, they undergo what researchers call a “sampling period.” They play a variety of sports, usually in an unstructured or lightly structured environment; they gain a range of physical proficiencies from which they can later draw; they learn about their abilities and proclivities; and only later do they focus in and ramp up technical practice in one area.

Yeah, but that might only be true of sports, right? Nope. Same pattern is evident in music.

From Range:

…the students classified as exceptional by the school came from less musically active families compared to less accomplished students, did not start playing at a younger age, were less likely to have had an instrument in the home at a very young age, had taken fewer lessons prior to entering the school, and had simply practiced less overall before arriving – a lot less.

And what were the best music students like? They “turn out to be those children who distributed their effort more evenly across three instruments.” Again, more Roger, less Tiger.

But maybe your kid, like most kids, isn’t going to be a pro athlete or part of an orchestra. Doesn’t matter. We see a similar principle in normal jobs after college.

From Range:

One study showed that early career specializers jumped out to an earnings lead after college, but that later specializers made up for the head start by finding work that better fit their skills and personalities.

10,000 hours is good. But they don’t have to happen between ages 0-10. In fact, they shouldn’t.

(To learn more about how you and your children can lead a successful life, check out my bestselling book here.)

Alright, so what else does it take for you to end up in the Cooperstown of parenting? Well, learning in school is critical. What’s the problem most moms and dads face here?

Well, the problem might be that your kids are doing too well in school.

Yeah, you heard me…

2) Real Learning Is Slow And Frustrating

I’ll repeat that: “the problem might be that kids are doing too well in school.”

I’m sure you have a suppressing-a-fart expression on your face right now. Hold on, I’ll explain…

Good grades are wonderful. But if they’re coming fast and easy, chances are your kid isn’t really learning all that much that they’re really going to retain. The research is clear: to really learn, studying must be hard. They even have a clever name for this: “desirable difficulties.”

From Range:

“Some people argue that part of the reason U.S. students don’t do as well on international measures of high school knowledge is that they’re doing too well in class,” Nate Kornell, a cognitive psychologist at Williams College told me. “What you want is to make it easy to make it hard.” Kornell was explaining the concept of “desirable difficulties,” obstacles that make learning more challenging, slower, and more frustrating in the short term, but better in the long term.

So good performance early can be bad. Sound crazy? Oh, it gets crazier… As a corollary, “great” teachers are often terrible.

From Range:

The Calculus I teachers who were the best at promoting student overachievement in their own class were somehow not great for their students in the long run. “Professors who excel at promoting contemporaneous student achievement,” the economists wrote, “on average, harm the subsequent performance of their students in more advanced classes.”

Are their students all doing well? Not struggling? Then the children probably aren’t retaining as much as they should be. Grades and long term learning are not the same thing. You know this first hand…

How many times did you cram for a test, do fine, but then 24 hours later you couldn’t remember a single thing you studied? Exactly.

That wasn’t early onset dementia. Studies show learning too fast or too easy doesn’t stick. Struggling is essential. In fact, trying hard and being wrong can be better than initially being right.

From Range:

In one of Kornell’s experiments, participants were made to learn pairs of words and later tested on recall. At test time, they did the best with pairs that they learned via practice questions, even if they had gotten the answers on those quizzes wrong. Struggling to retrieve information primes the brain for subsequent learning, even when the retrieval itself is unsuccessful.

Yes, it’s very impressive to have a kid easily getting all A’s. But if you really want your child to grow up to be a top performer, you don’t want your kid to be a prodigy.

If life success all came down to doing well early, savants would rule. So how many savants have become “Big-C creators” who had a major impact on their field?

Zero.

From Range:

As psychologist Ellen Winner, one of the foremost authorities on gifted children, noted, no savant had ever been known to become a “Big-C creator,” who changed their field.

If you can knock out 20 bench presses with X weight and not break a sweat, that might look good but would you expect to get bigger and stronger? No, the weight’s clearly too light for you. If you’re not struggling at all, your muscles aren’t going to get much stronger.

Same goes for your kid’s brain.

(To learn the 10 steps to raising happy kids, click here.)

Okay, on to the next tip from David. Let’s get focused. Let’s get specialized. Let’s get…

Meh. Let’s not…

3) Too Much Specialization Makes You Narrow

We live in a world of increasing specialization. Doctors don’t even specialize in oncology anymore, now they specialize in particular cancers.

Make sense, right? Hard skills, clear roles, every single thing pointed toward that one goal. There is no doubt this is good for a resume. But it turns out it’s not necessarily good for a kid’s brain or their future. Don’t trust me; trust James Flynn…

Flynn is such a big deal that he even has an effect named after him. “The Flynn effect” shows that human beings have been getting smarter over time. (Yeah, I know you have plenty of evidence to the contrary, wiseguy, but just roll with me, okay?)

Average IQ is pegged at 100 but the IQ elves have had to keep readjusting the curve to keep it at 100 because people keep scoring higher. But why are we getting smarter?

Turns out it’s due to the ability to think abstractly. People in industrialized nations have gotten sharper because our thinking has become more broad, more abstract, less narrow and concrete. This allows us to adapt and apply our knowledge to new domains, an ability that is important now and will continue to be in the future.

From Range:

…premodern villagers relied on things being the same tomorrow as they were yesterday. They were extremely well prepared for what they had experienced before, and extremely poorly equipped for everything else. Their very thinking was highly specialized in a manner that the modern world has been telling us is increasingly obsolete. They were perfectly capable of learning from experience, but failed at learning without experience. And that is what a rapidly changing, wicked world demands – conceptual reasoning skills that can connect new ideas and work across contexts. Faced with any problem they had not directly experienced before, the remote villagers were completely lost. That is not an option for us. The more constrained and repetitive a challenge, the more likely it will be automated, while great rewards will accrue to those who can take conceptual knowledge from one problem and apply it in an utterly new one.

Taking all engineering courses and no liberal arts or business classes will make sure your daughter is a great engineer. But it will probably also make sure she never becomes CTO.

Kids need to learn a variety of things and how to make connections between them.

From Range:

Modern work demands knowledge transfer: the ability to apply knowledge to new situations and different domains… Research on thousands of adults in six industrializing nations found that exposure to modern work with self-directed problem solving and nonrepetitive challenges was correlated with being “cognitively flexible.”

And this is what we see in top performers. Yes, they specialize, but they have wide-ranging interests, providing a good amount of mental crop rotation to keep their cognitive soil fertile.

From Range:

Scientists and members of the general public are about equally likely to have artistic hobbies, but scientists inducted into the highest national academies are much more likely to have avocations outside of their vocation. And those who have won the Nobel Prize are more likely still. Compared to other scientists, Nobel laureates are at least twenty-two times more likely to partake as an amateur actor, dancer, magician or other type of performer. Nationally recognized scientists are much more likely than other scientists to be musicians, sculptors, painters, printmakers, woodworkers, mechanics, electronic tinkerers, glassblowers, poets or writers, of both fiction and nonfiction. And, again, Nobel laureates are more likely still.

Ever meet someone who is a total one-trick pony? Great at their role, terrible at everything else? Don’t let your kid be that. Teach your pony a few more tricks.

(To learn how to deal with out-of-control kids — from hostage negotiators — click here.)

Are you still reading? That makes me happy. You have grit. Those people who stopped reading don’t. And anything that keeps you reading my stuff must be inherently good…

Um… right?

4) When You’re Young, Quit May Be Better Than Grit

Boy, do we hear a lot about grit these days. Yes, it’s important. This post wouldn’t very good if I didn’t finish it. But if you think grit is the end-all be-all, well, now you’re speaking fluent crazy.

Sometimes grit can be a negative. Sometimes grit isn’t even grit – it’s just stubbornness, fear of change, or the sunk cost fallacy working overtime.

This is an important distinction to make — not only because it allows me to rationalize a lot of my own past flaky behavior — but because it can help us understand why the silly decisions young people make aren’t always that silly.

Young people take risky, crazy jobs that parents think are a waste of time. But economists know their behavior actually makes sense. Are you going to try to make it as an actor or professional athlete at 50 when you’re married with kids and a mortgage? I sure hope not.

When you’re young, trying something that’s high-risk, high-reward can make sense. And even if it doesn’t work out, you learn things about yourself and the world really fast, which benefits you later.

From Range:

The expression “young and foolish,” he wrote, describes the tendency of young adults to gravitate to risky jobs, but it is not foolish at all. It is ideal. They have less experience than older workers, and so the first avenues they should try are those with high risk and reward, and that have high informational value. Attempting to be a professional athlete or actor or to found a lucrative start-up is unlikely to succeed, but the potential reward is extremely high. Thanks to constant feedback and an unforgiving weed-out process, those who try will learn quickly if they might be a match, at least compared to jobs with less constant feedback. If they aren’t, they go test something else, and continue to gain information about their options and themselves.

But seriously, shouldn’t young people stop wasting time on silly pipe dreams and focus on what is really likely to make them successful and fulfilled?

Well, what happens when you actually study people who are successful, fulfilled, with a career they really love, one perfectly matched to their personality?

From Range:

Todd Rose, director of Harvard’s Mind, Brain, and Education program, and computational neuroscientist Ogi Ogas cast a broad net when they set out to study unusually winding career paths. They wanted to find people who are fulfilled and successful, and who arrived there circuitously. They recruited high fliers from master sommeliers and personal organizers to animal trainers, piano tuners, midwives, architects and engineers. “We guessed we’d have to interview five people for each one who created their own path,” Ogas told me. “We didn’t think it would be a majority, or even a lot.” It turned out virtually every person had followed what seemed like an unusual path.

We think of fulfilling careers as a straight line and any deviation as an error. Actually, straight lines are the exception, especially with people who go on to be very successful and happy. Your first job isn’t a perfect fit any more often than the first date you go on turns out to be with your soulmate.

Being a bit flaky can be good, especially when you’re young, because it gives you the chance to learn about yourself in different environments. As London Business School professor Herminia Ibarra says, “Be a flirt with your possible selves.”

(To learn how to raise emotionally intelligent kids, click here.)

Okay, we’ve learned a lot from David. Time to round it all up and get some tips that can help you, the parent, live a happier, more successful life…

Sum Up

Here’s how to make your kids successful:

- Children need a sampling period: Raise your kids like a Roger, not a Tiger.

- Real learning is slow and frustrating: I have deprived you of lasting knowledge by making this easy to read and the guilt is overwhelming.

- Too much specialization can make you narrow: A one-trick pony often becomes a very dumb, boring, unsuccessful horse.

- When you’re young, quit may be better than grit: Skip the youthful mistakes and they become middle-aged mistakes — where they’re a lot more costly.

This post is focused on kids because that’s where this knowledge is most useful. But let me tell you a little secret…

It all applies to you too. Keep sampling. Keep learning. Don’t get narrow. Don’t be afraid to quit something that isn’t working and try something new.

The media just loves to tell stories about young wunderkinder like Mark Zuckerberg… but just like Tiger Woods, his path is the exception, not the rule.

From Range:

…a tech founder who is fifty-years old is nearly twice as likely to start a blockbuster company as one who is thirty, and the thirty-year old has a better shot than the twenty-year old. Researchers at Northwestern, MIT, and the U.S. Census Bureau studied new tech companies and showed that among the fastest growing start-ups, the average age of a founder was forty-five when the company was launched.

Your story isn’t over. You still have more chapters left. A few more plot twists. Maybe even a surprise ending.

From Range:

Compare yourself to yourself yesterday, not to younger people who aren’t you. Everyone progresses at different rates, so don’t let anyone else make you feel behind. You probably don’t even know where exactly you’re going, so feeling behind doesn’t help. Instead, as Herminia Ibarra suggested for the proactive pursuit of match quality, start planning experiments.

Keep trying crazy experiments. They bring new color to your life. As Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes said:

“It is an experiment; as all life is an experiment.”

Join over 330,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

New Neuroscience Reveals 4 Rituals That Will Make You Happy

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert